Madrid

Cayón is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition of Philippe Decrauzat (Lausanne, Switzerland, 1974) since he joined the gallery: Inattentional blindness. The artist asked the French writer Muriel Pic for a text to crystallise his thoughts and his vision of the exhibition, which we propose below.

In the palm of their hand, the prestidigitator places a small cork ball that magicians call nutmeg because it resembles the nut from the Banda Islands, which is well known for its psychoactive properties once ingested in a certain dose. As they perform their magic trick, they close their hand and dutifully turn their fist in front of the spectator. That being done, they open it quietly and show their palm empty or with a coin instead of nutmeg.

The spectators were taken aback, because they never took their eyes off the illusionist’s hand. In fact, they missed something, or rather something that kept their attention elsewhere. They were the victim of what psychologists call inattentional blindness.

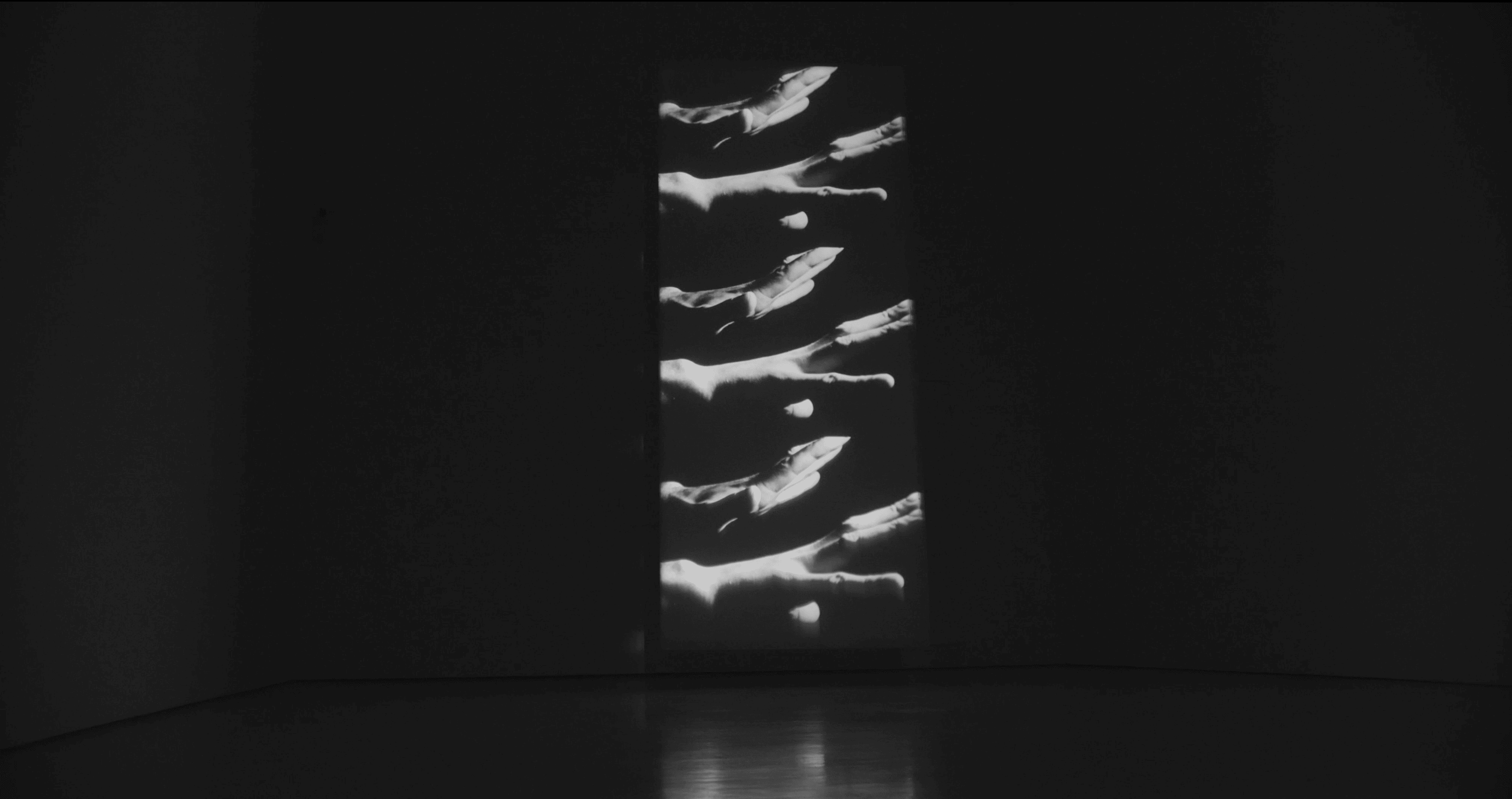

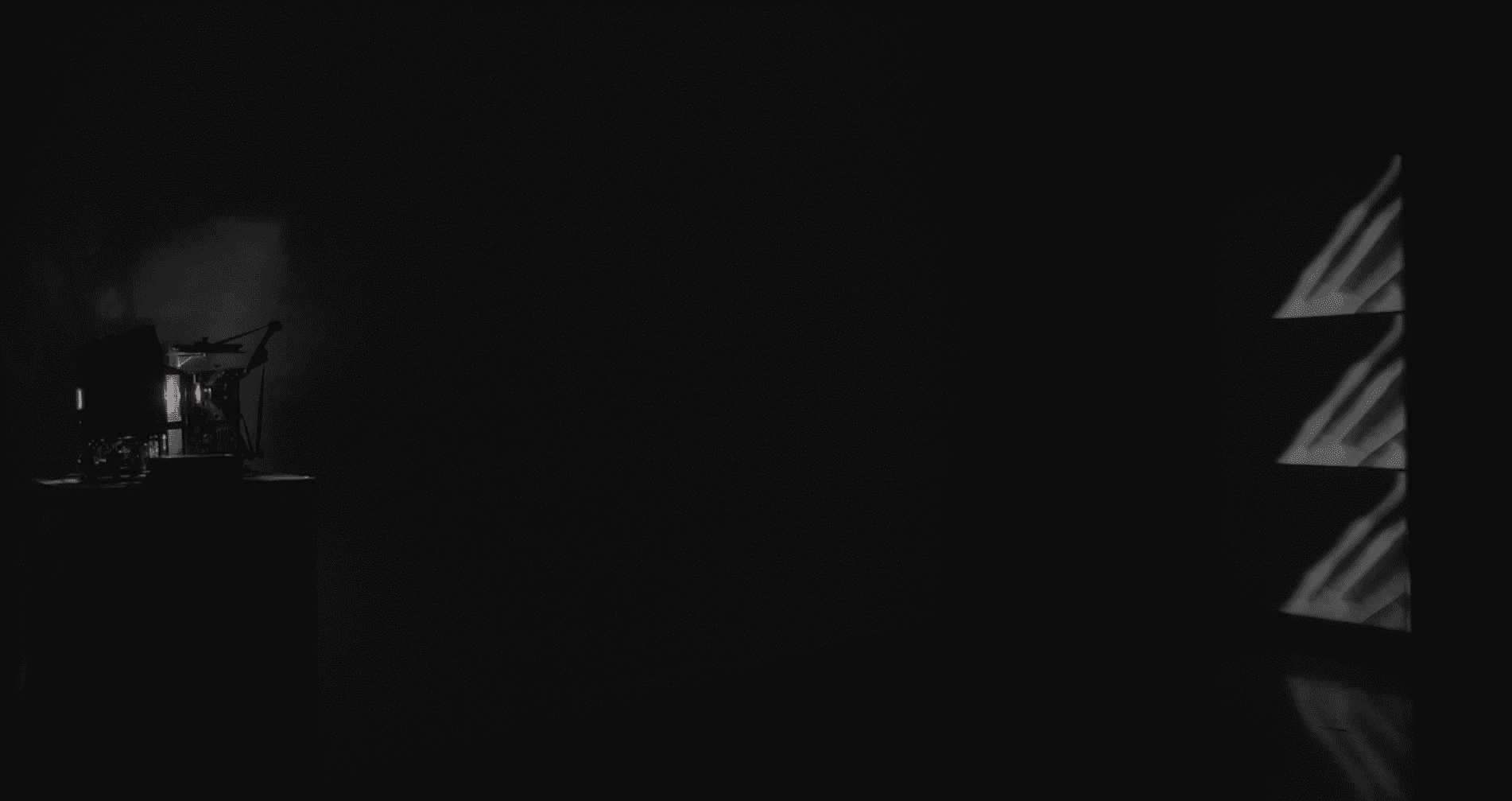

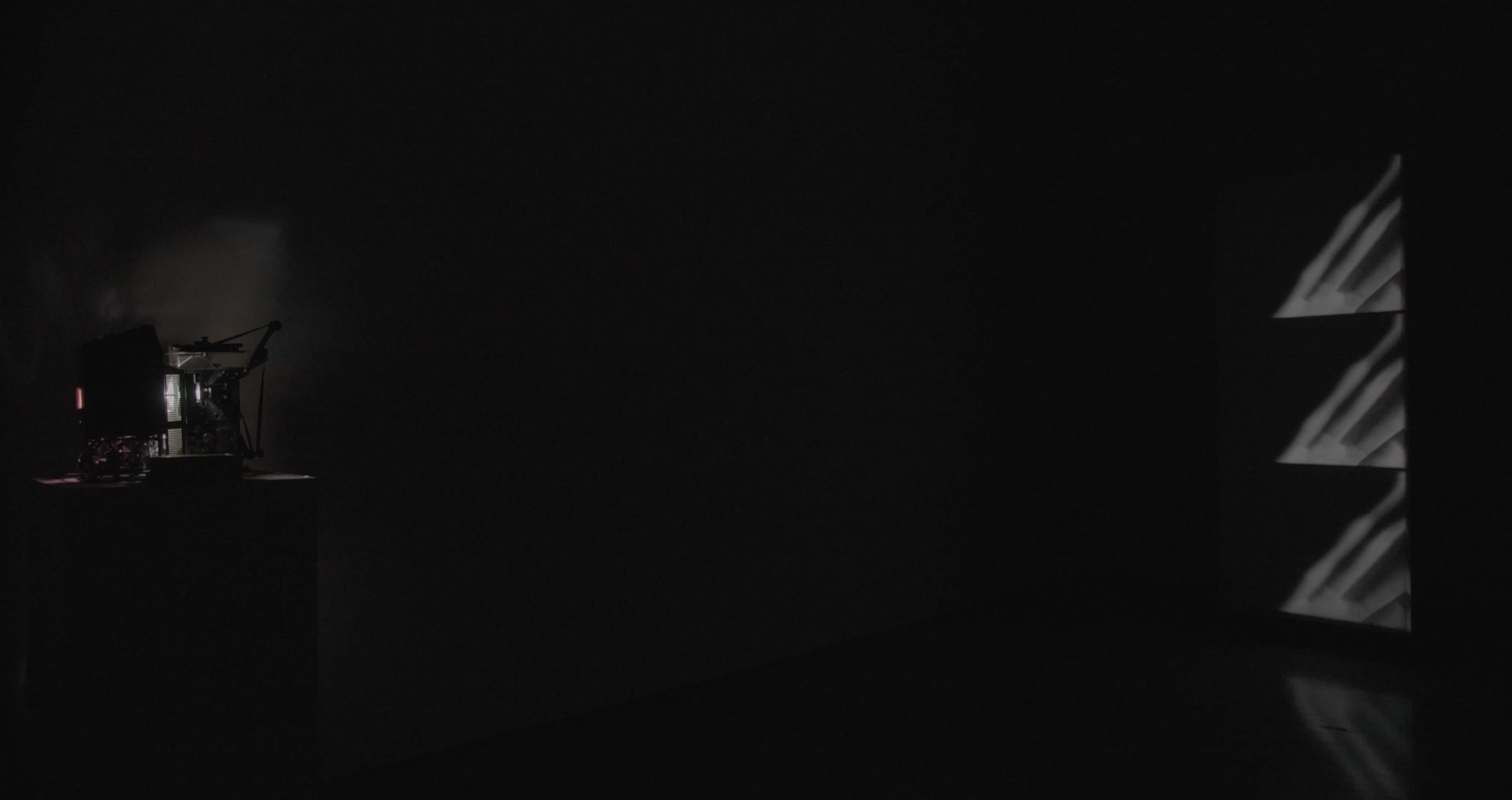

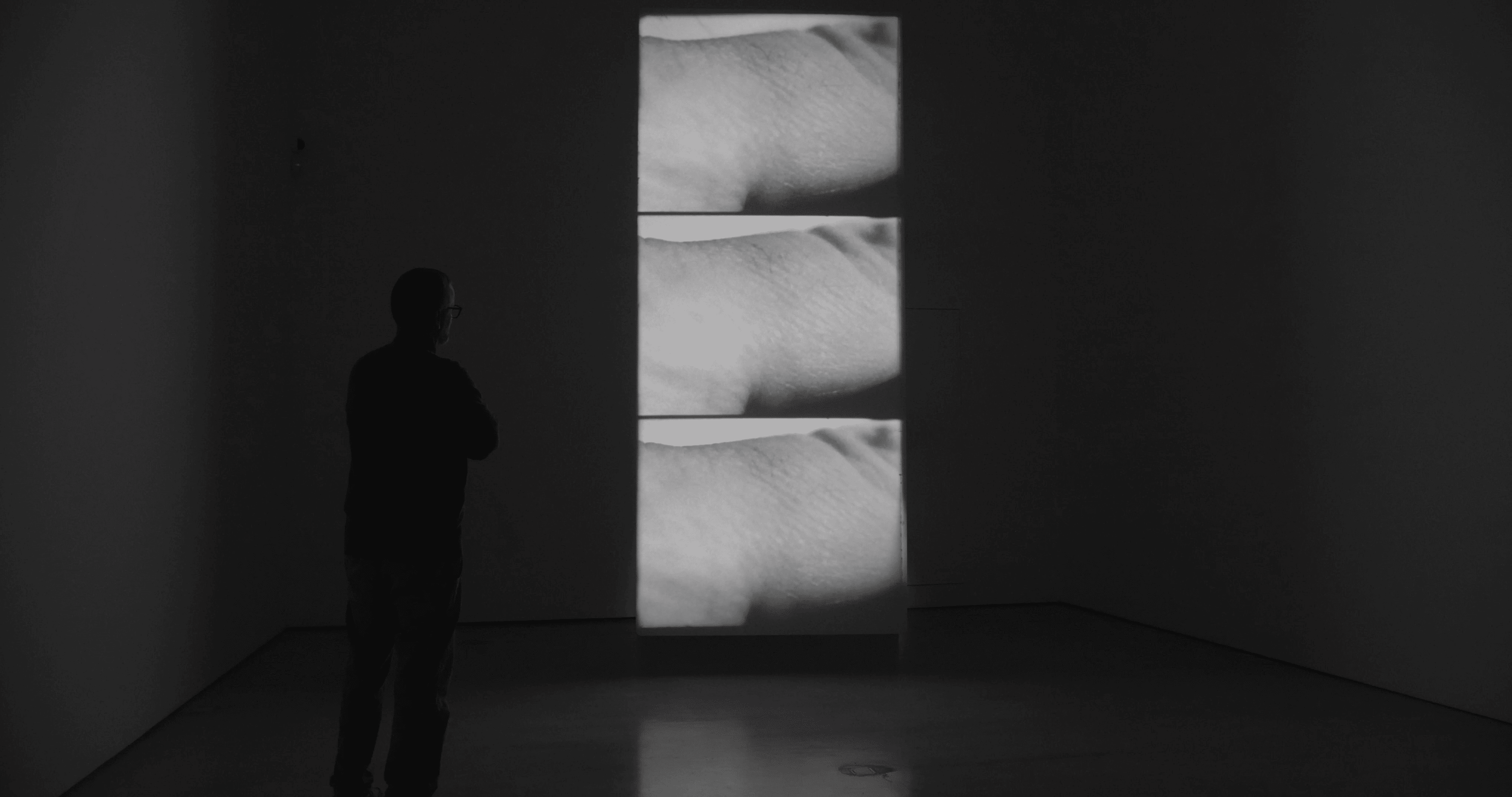

Philippe Decrauzat’s work, which bears this title, is a black-and-white film made on 16mm film. Its referent is the prestidigitation scene. Painted in the painting ‘falsely’ attributed to Hieronymus Bosch, The Conjurer, at a time when Holland had a monopoly on the nutmeg trade, it was also the subject of a book on experimental psychology written in 1894 by Alfred Binet.

To unravel the mystery of the illusionist, Binet asked Georges Demenÿ, a close friend of Etienne-Jules Marey, to carry out a chronophotographic study of magicians’ hands as they performed various passes and card tricks. By breaking down the gestures into a series of still images, he hoped to make visible what was not visible to the naked eye. This visual study, carried out to understand the phenomena of attention, touches on questions that are currently occupying neurosciences. It is the referent from which Decrauzat opens us up an elsewhere of images.

For Inattentional blindness, a new kind of projector, transformed by the artist, projects three successive images simultaneously. The device is based on the principle of chronophotography, which breaks down movement into still images. But there’s more: the projection makes me think of the cuts my eyelids make in my vision, my brain continually editing fragments of images to enable me to perform the act of seeing.

With Inattentional blindness, the act of seeing is open to the infinite: what is this fluttering hand, these interlocking bodies, this landscape of tomorrow trying to tell me? With Decrauzat, there is no science without dreams, no technology without magic, and vice versa. Art dreams accurately with science.

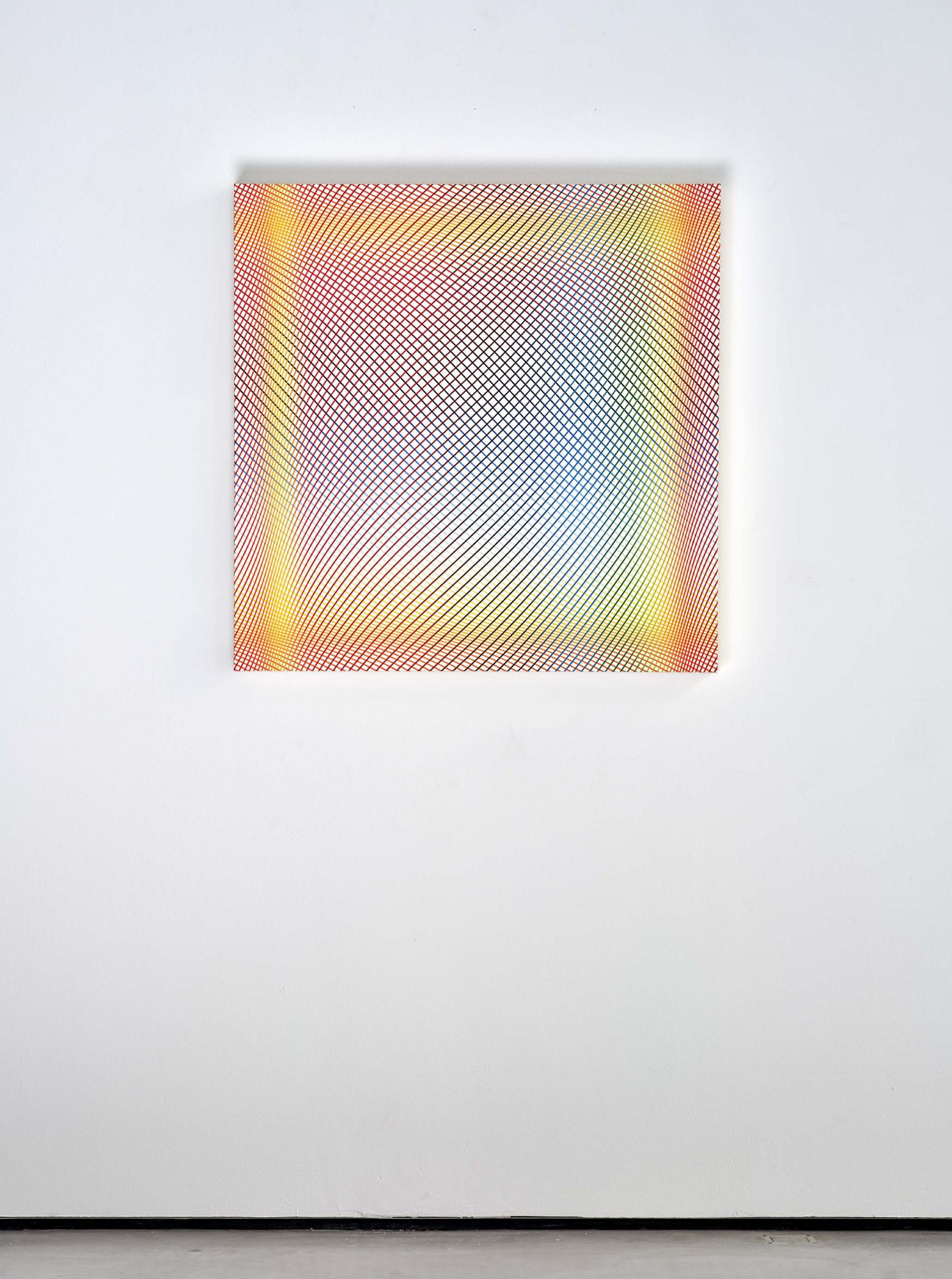

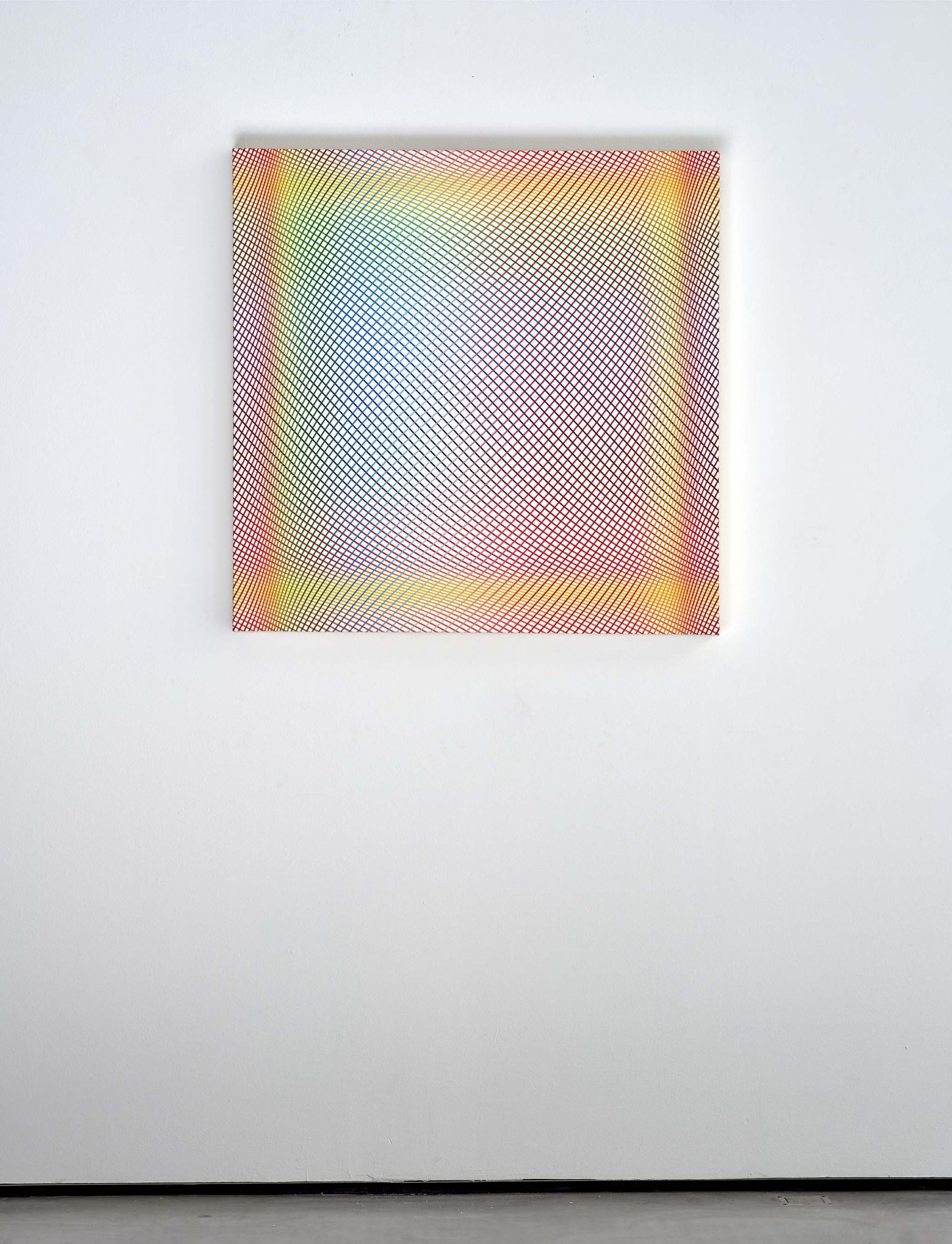

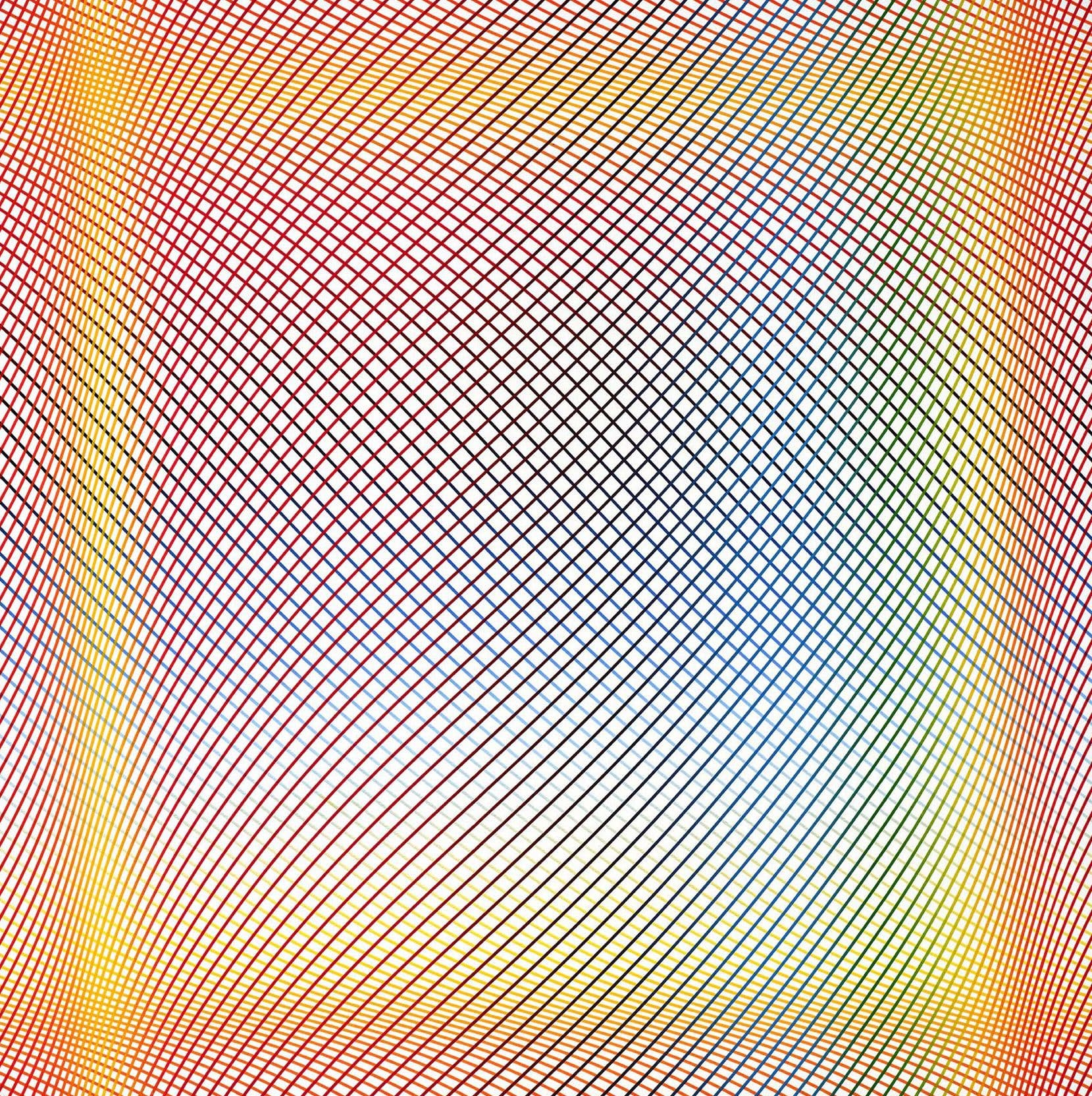

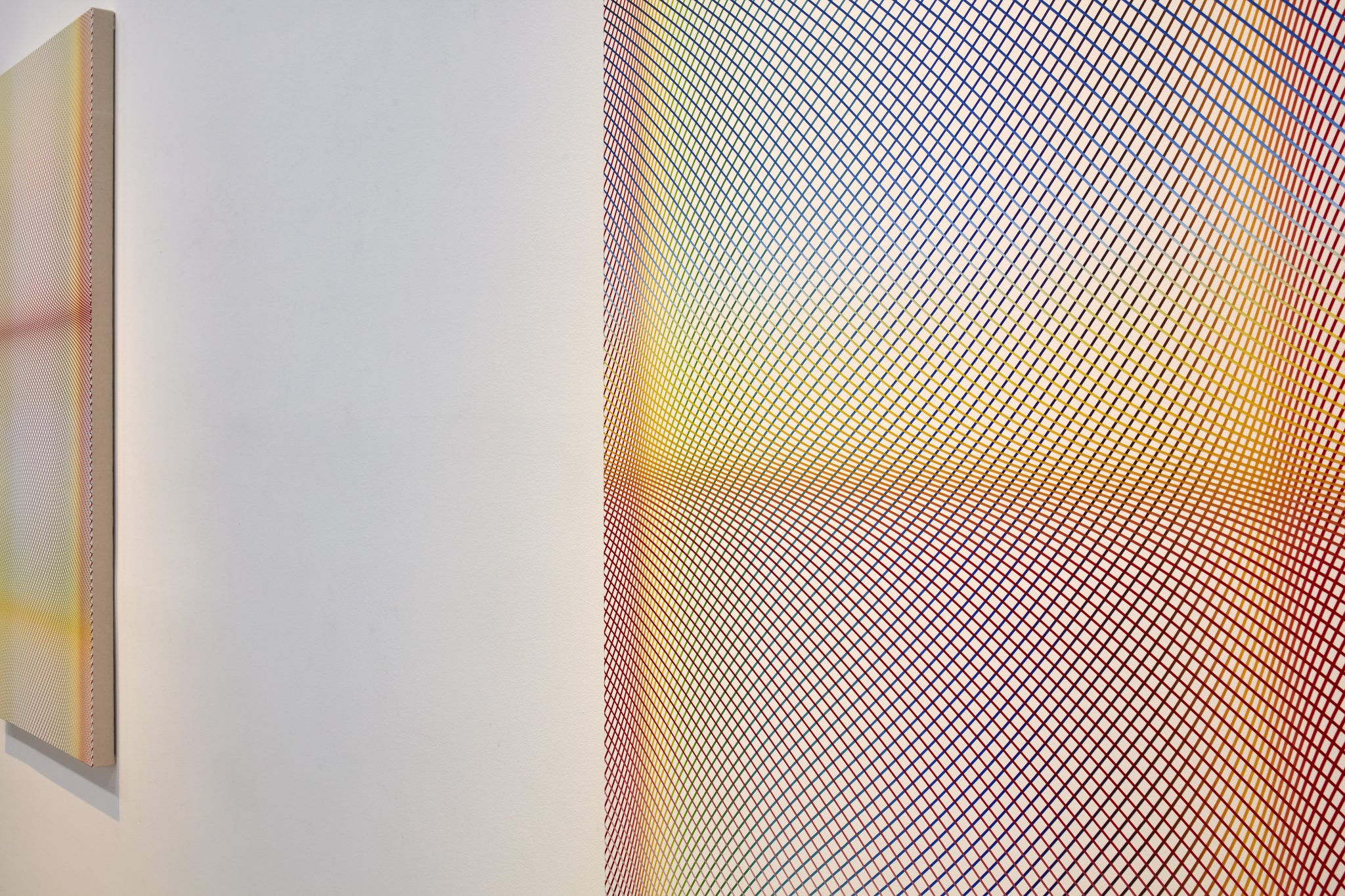

Alongside the film, the artist presents a series of coloured paintings. Having just emerged from my black-and-white meditations, I can’t help but wonder: what is this screen of colours that wasn’t there before? It’s Screen. A game, a pleasure, a joy of perception. An illusion made into an image thanks to a rigorous understanding of optics. A painting that comes to life on the nervous screen of my brain. A work that I look at and that envelops me and penetrates me with all my senses. A film in which I am the phenomenological camera.

With Screen, depth moves towards the surface, curves give birth to straight lines, and all this reciprocates. The mesmerized viewer can only repeat: to be is to be perceived. Admit it, it’s not every day you ask yourself a metaphysical question in front of a screen.

In general, your brain doesn’t think about either the perceiving or the perceived. It automatically scans pages and assimilates content. They’re often fake, where everything is fake but based on the real thing. With Screen, it’s exactly the opposite. Everything you see is real, although based on fake.

Screen and Inattentional blindness are plastically very different works, but they stem from the same sensation: a point of blindness.

Somewhere between an experience of extra-lucidity, which consists in seeing beyond what blinds us, and a critical reflection on what blinds us to fool us, Decrauzat’s art addresses the viewer with sovereign simplicity: a hand opens, a hand closes, a straight line appears, a curve disappears.

My eyelid blinks, the nutmeg disappears, my eyelid blinks, the stone of madness appears. Is the illusionist’s nutmeg psychoactive? I lose myself in the moiré and iridescence, I’m on the verge of hallucination. Each time, I miss something of the real, my attention held elsewhere; each time, I have the novel experience of seeing what I usually forget to perceive: the film of sensation alone.

Muriel Pic